FSA launches long-awaited raw milk review – an informed choice?

The Food Standards Agency (FSA) has announced the public consultation stage following a policy review of sales of raw drinking milk. The consultation pack which accompanied the announcement last Thursday, 30 January, extends to 191 pages[1] of detailed information and sets out four options for the future. The good news is that the FSA has expressed a preference for continuing raw milk sales under the fourth of the following four options:

Option 1: Do nothing

Option 2: All milk to be pasteurised prior to sale

Option 3: Allow sales of raw drinking milk from all outlets

Option 4: Introduce measures to harmonise and clarify current controls.

In short, in a choice between the status quo, either extreme and somewhere in the middle, a whisker away from the status quo it is the last of these which is preferred by the FSA at this stage. The law as it stands says that sales can only be direct from the farm to the final consumer which under Option 4 would mean:

- Raw drinking milk from cows: No change to current domestic legal restrictions, but the FSA to publish guidance clarifying the intention of the law.

- Raw drinking milk from other species: Introduce same sales restrictions as for cows’ milk through legislation or a voluntary code of practice.

- Labelling: Amended mandatory health warning consistent across England, Wales and Northern Ireland and all species.

- Other routes of sale: Direct from farm, farmers’ markets and direct online internet sales - no change.

Due credit to the FSA for stating a clear preference at the outset and one which sees a future for the continued supply of raw drinking milk. No doubt the FSA has been heavily influenced by the complete absence of any evidence pointing to the need for substantive change, but nonetheless welcome while acknowledging it is only a preliminary view.[2]

Evidence of risk to health

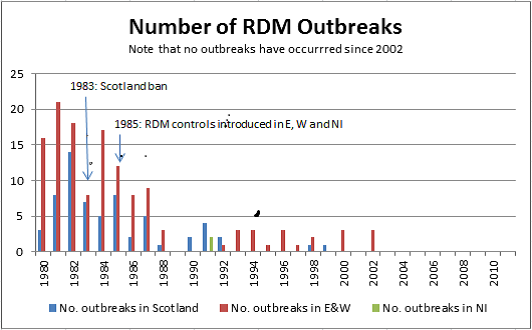

The evidence speaks for itself. There have been no reported outbreaks of illness associated with raw drinking milk in the UK since 2002 as illustrated in the table below:

Furthermore, several other factors should be noted, including:

- The outbreaks in the 1990s and early 2000s were very small in comparison to earlier outbreaks.[3]

- National surveillance data for VTEC (pathogenic E. coli) infection reveals that the overwhelming majority of cases of VTEC infection (97-99%) do not report raw milk consumption. The small number which do (1-3% or 51 out of 2,384 cases in England) also report exposure to other sources of infection. In short, raw milk does not cause significant numbers of cases of VTEC illness in the UK.[4]

- The latest surveillance data for raw drinking milk is from surveys carried out between 1995 and 1999 indicated Campylobacter spp, E. coli O157, Salmonella spp and L. monocytogenes present in up to 2, 0.5, 0.5 and 3% of samples respectively. If still present at these levels it would support the view that the likelihood of exposure to pathogens is low. It is not unusual for large surveys of ready to eat foods to find occasional presence of pathogens similar to these levels.[5]

Shortcomings in the consultation

Where the consultation pack falls short, however, is in at least two significant respects. First, it fails to establish a core principle or principles guiding the implementation of the legislation and, second, provides no comparative assessment of risk associated with raw milk as against other foods.

Integrity of the food chain

The first follows from a reading of the legislation (The Food Safety and Hygiene (England) Regulations 2013, Schedule 6) which makes it clear that what it seeks to protect is the integrity of the food chain from farmer to consumer in a very direct way. The farmer retains ownership and control over the milk, and so remains responsible for milk quality, from its source in the production unit until delivered into the hands of the consumer. A food chain can get no shorter or have greater integrity.

The one exception provided for in the regulations covers a person operating a milk round who takes delivery of milk in sealed containers.

So rather than try and provide for all conceivable situations, better to establish principles and illustrate with some examples. The FSA would be quick to point out that it is the courts which are the final arbiters of what is and is not lawful and they are adept at extracting the principles and purpose of legislation and applying them in a contemporary setting as routes to market evolve and new ones emerge. This would provide a rationale and a framework which all could understand, accept and work within.

The failure to establish clear principles is likely to lead to continuing confusions of the sort which the FSA aims to avoid and which have been written about on this blog elsewhere.

Raw milk is not a high risk food

The second significant shortcoming is that little or no information is provided about where raw milk stands as, for want of a better description, a ‘risky food’. The comparison is always made with pasteurised milk which is an inherently safe product. If the risk of contracting an infection from pasteurised milk is very small, even a 100% (purely for the sake of argument since the true figure is not known) increase on that level of risk remains very small. In order to make an informed choice it is necessary to get things into perspective, how does raw milk rank against a range of foods we eat?

In May last year Canadian researcher Nadine Ijaz, in a presentation made to the British Colombia Centre for Disease Control, demonstrated how inappropriate evidence has long been mistakenly used to affirm the myth that raw milk is a high risk food. The conclusion?

“… public health bodies should now update their policies and informational materials to reflect the most high-quality evidence, which characterizes this risk as low.”

In the US, as Ijaz points out, green leafy vegetables are the most frequent cause of foodborne illness.

77% support continued raw milk sales

Meanwhile, it is encouraging to observe, from survey data commissioned by the FSA, that 77% of those surveyed supported the continued sales of raw drinking milk, while 20% expressed interest in buying or consuming raw milk and 3% do so regularly.

The consultation pack covers much more to be explored in the coming weeks, not least raw milk controls over milk from species other than cows – goats, sheep and buffalo, the evidence for reported health benefits and how small dairy farms could be supported.

This is an important consultation, not simply for the future availability of raw milk, but the whole question of consumer choice in the food we eat. Let this not be a missed opportunity – make your voice heard!

Meanwhile, feel free to post your comments and questions below. The consultation closes 30 April 2014.

Details of the consultation can be found here: Impact Assessment on the review of the controls governing the sale and marketing of unpasteurised, or raw drinking milk and raw cream (RDM) in England

There is more information in the Artisan Food Law Library on the law relating to raw milk here: Dairy: Raw Drinking Milk

Photo: © @hookandson www.hookandson.co.uk Est. 1959. Raw milk fresh from the farm, direct to your door.

[1] Food Standards Agency, Impact Assessment on the review of the controls governing the sale and marketing of unpasteurised, or raw drinking milk and raw cream (RDM) in England, 30 January 2014

[2] FSA (2014), p4, para 10

[3] FSA (2014), p10, para 18

[4] FSA (2014), Annex B, p19, para 53 to 54

[5] FSA (2014), p20, para 56